A Distinctive Past

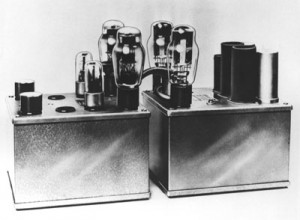

In June 1949, Audio Engineering magazine (later known as Audio) called readers’ attention to a new amplifier “of unusual capabilities, incorporating a completely new design.” It wasn’t just the amp that was unusual. McIntosh, the fledgling firm that built it, would soon transform itself into one of the high fidelity industry’s most formidable companies.

Though some contemporary components continue to carry grand old names, precious few meet the exacting standards set by the vintage products that originally wore them. McIntosh is a notable exception. By all measures, its components are superb and rank among the most exciting high end audio and A/V components made anywhere.

If Frank McIntosh and Gordon Gow, who did so much to create the rich heritage that underpins the firm, are looking down, they’re surely proud. Both would agree the McIntosh of today is worthy of the traditional blue-tinted meter that has in effect become its corporate heraldic crest.

Not surprisingly, Frank McIntosh’s background included experience at Bell Laboratories, which was in its day the fountainhead of electronics research. Nor is it surprising that he was an accomplished cellist who, while still in high school in his home state of Nebraska, formed a string trio with his brothers. McIntosh could have gone on to study music on a college scholarship, but he opted for engineering instead.

In 1946, McIntosh began setting up a service to provide background music, then a relatively recent innovation that had been used during World War II to keep factory workers alert. He had two very distinguished colleagues in the venture: Frank Stanton, who was just starting his long tenure as president of CBS, Inc., and J. Leonard Reinsch, a former White House press secretary who had served both Roosevelt and Truman and would go on to arrange the historic TV debates between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. The background music business required amplifiers that delivered high power along with low distortion, and because there weren’t any that combined both attributes, McIntosh decided to develop one.

He tapped Gordon Gow to help. Gow hadn’t studied engineering formally, but he was an ardent reader and auto-didact who, like McIntosh himself, had experience in radio station engineering. He acquired even more knowledge and experience in the Royal Canadian Air Force and, after serving in several countries during World War II, was awarded an MBE for his radar-related inventions. (The initials stand for Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, an honor conferred by the reigning English monarch on the advice of the nation’s government.)

Gow was assigned to Washington, D.C. when McIntosh met and hired him just after the war. He would remain at McIntosh for more than four decades, and he was at the company’s helm when he died of a heart attack at his upstate New York home in 1989. Frank McIntosh, who had retired to Arizona in the late 1970s, died the following year.

By 1948, an amplifier output stage incorporating McIntosh’s groundbreaking Unity Coupled tube circuit had been assembled, and five patent applications had been filed. As of today, the company has earned a total of 34 patents, and the Unity Coupled principle remains important; with refinements, it has been used in every tube amplifier McIntosh has ever made. McIntosh and Gow described the circuit in a co-bylined article that appeared in the December 1949 issue of Audio Engineering, and after the amplifier that featured it was demonstrated for the Institute of Radio Engineers, NBC ordered 50 of them. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation also placed a major order.

In 1951, McIntosh moved its Maryland-based manufacturing facility to Binghamton, New York, where the company remains headquartered and where it still builds all its products. By then, McIntosh had developed a preamplifier and was running regular ads in the electronics press. Its products were also listed in specialty catalogs from such firms as Chicago-based Allied Radio and Fort Orange Radio in Albany, New York.

Sidney Corderman, who would become another important force at McIntosh, signed on at that time and took charge of engineering, research and development. Because the Binghamton area was also home to IBM, Link Aviation and General Electric, it was a cornucopia of qualified help, Corderman has explained. In a recent interview with the noted audio writer Ken Kessler, he described the environment in which McIntosh and other pioneering audio firms then operated.

“It was the broadcast stations and commercial users who really appreciated those first amplifiers,” he noted. “They couldn’t believe that the performance was what was claimed of them, primarily the sound, the low distortion, the high power. The first amplifier [produced] 50 watts of power, 20 Hz to 20 kHz, and with less than 1% distortion. It was exceptional. People in the know didn’t believe it was possible.”

Given the limited size of the hi-fi market back then, it made sense for Frank McIntosh to have other irons in the fire. He owned a separate company that made products for government and industry, and in the early days of the Atlas space program it provided ground instrumentation amplifiers. (That firm was ultimately purchased by Mack Electronics, part of the Mack Truck operation.) He also catered to museums, some of which — America’s celebrated National Gallery of Art among them — used devices incorporating standard McIntosh power amplifiers to play recorded information about exhibits for visitors.

Eventually Sidney Corderman built an engineering dream team at McIntosh that included, among others, Tom Rogers and Larry Fish. Rogers, who stayed with the company for nearly four decades, did much of the mechanical and industrial designing that McIntosh products incorporated, and Fish, on staff for 31 years, managed the engineering department as well as doing some tuner design.

By the time Dave O’Brien arrived in 1962, the company’s consumer clinic program, an important key to establishing it as a leader in audio electronics, was under way. Clinics were held in McIntosh dealer showrooms around the nation, and during the program’s first years people were invited to bring in any amplifier, regardless of brand, so it could be tested to determine whether it met the manufacturer’s published power output specification. (Though McIntosh was an exception, amps in those days often didn’t.) As the scope of the program widened, a McIntosh amp or preamp that was brought in and wasn’t performing properly would be repaired then and there.

O’Brien ran the clinic program for 30 years. “I figure that I’ve had my hands on a quarter-million pieces of gear,” he later reminisced, “and probably talked to one million owners…many times checking units that belonged to the heirs or descendants of the original buyers.” Eventually, with McIntosh products increasingly more reliable and too sophisticated for on-the-spot servicing, O’Brien decided clinics should restrict themselves to testing and evaluation only, and when he retired from the road in 1992 the program became part of McIntosh’s enviable history.

Learn More About Hi-Fi’s Oldest Audiophile Brand By Clicking These Links

Important McIntosh Benefits Great McIntosh Products